In his 2009 work, The Accidental Guerrilla, David Kilcullen summed up the different communication approaches by Al Qaeda-backed insurgents and the Western-led Coalitions seeking to defeat them. “We use information to explain what we’re doing on the ground. The enemy does the opposite — they decide what message they would send and then design an operation to send that message.” The observation was not new; it had been described in similar fashion among the Strategic Communication and Information Operations community since the commencement of the Global War on Terror and earlier and is often referred to as “narrative-led operations.” Kilcullen did however bring the concept to main-stream military thinking. He, like many before him, advocated for the use of information as a central component of planning and operations rather than as an adjunct attempting to translate activities and incidents occurring in the physical domain into an aspirational statement. The latter approach, unfortunately tried and tested for the past decade, leads to the now famous “say-do gap.”

Narrative has become a buzzword as leaders, civilian and military alike, attempt to create an enduring ‘story’ to set the framework through which operations are undertaken.

The rise of Daesh and its embrace of communications technology to send its message to a global audience has many organisations rethinking their approach. Narrative has become a buzzword as leaders, civilian and military alike, attempt to create an enduring ‘story’ to set the framework through which operations are undertaken. That we are still focused on creating our narrative six-months into this operation perhaps highlights that Kilcullen’s observation was not as widely disseminated as his book-sale figures would have us believe.

So what is a narrative?

The rise in popularity of the term ‘narrative’ during past 12 months has directly coincided with an increased misunderstanding of what it actually means. Like the ‘StratCom’ era of 2004 onwards, ‘narrative’ has become a corporate buzzword that has multiple meanings depending on who is using it. Some use narrative as a euphemism for talking points around a single issue, incident or event. Others use narrative as a kinder, gentler, word for adversary propaganda. A small group segment out narrative by dissemination method. Some believe a narrative is one-time core statement while others approach it as an ever-evolving story arc. There are those that even confuse narrative for strategy. In reality a narrative is much simpler than this. Unfortunately that simplicity does not mean that generating and sustaining it is easy.

…a narrative describes the current state, what the proposed future state will look like and justifies the actions needed to get there.

A narrative provides the compelling foundation for communication efforts, not the communication effort itself. A narrative is a simple, credible and overall representation of a conceptual ideal designed to convey the organisation’s self-concept, values, rationale, legitimacy, moral basis and vision. A narrative informs and educates internal and external audiences and therefore is ‘translated’ in a cultural and attuned manner. It is the common reference point that should guide the development of all plans — communication and manoeuvre. In even simpler terms, a narrative describes the current state, what the proposed future state will look like and justifies the actions needed to get there. In military terms it sets the left and right limit of arc.

A key feature of narratives is that there is always more than one in circulation and in most cases they are competing for acceptance among similar target audiences. The pervasiveness of a narrative then becomes crucial if it is to act as a framework for follow-on communication activities and to support planning. Military planners seek to generate and sustain the ‘dominant narrative’ — the fundamental story or perception that has been established as valid in the minds of members of one or more target audiences — to support both strategy and operations. Moreover it is here that the struggle in creating an effective narrative plays out. In a modern democracy, narratives are genuinely political in nature, particularly immediately prior to, or early in conflict, and then again at its conclusion. Given the truism that all politics is local, early crafted attempts at a narrative are often focused almost solely on one target audience — the political party’s support base. This focus, while absolutely important to those making the difficult decision to commit national blood and treasure to a conflict, limits the narrative’s ability to meet the demands of the military or interagency force tasked with executing the assigned mission. Therefore an appropriate narrative must focus on more than one target audience. In the current Iraq conflict these target audiences include our own domestic populations, the Iraq population with its myriad ethnic, cultural and sectarian boundaries, coalition partners, regional nations impacted by the ongoing fighting and of course, the personnel we send into harm’s way. Importantly, the narrative must also address our adversary, the Daesh themselves and those disillusioned young men and women who are recruited from across the world by a false promise.

A narrative that is so aspirational that it is unrealistic, has failed before it is published.

The difficulty is that to be pervasive, a narrative must be something that is easily digested, no more than 200–300 words, and the complexity of modern conflict as is playing out in Iraq makes a simple explanation difficult. A good narrative does one of two things. It can unseat an existing or competing narrative by offering an attractive alternative or, it can assist in adding so much complexity to the adversary’s narrative that it loses its appeal. A good narrative provides the framework for a range of communication efforts, not the exact text of all communication efforts as some would like. A narrative has to be credible and that means incorporating some aspects that many would prefer were left unstated. In a recent essay, The Islamic State Through the Looking Glass, authors Peter Harling and Sarah Birke posited that the West has a tendency to “use vocabulary that is designed to be reassuring rather than true.” A poorly formed narrative can be easily critiqued, ridiculed and countered. A narrative that is so aspirational that it is unrealistic, has failed before it is published. An effective narrative to support operations should include some hard truths about how the situation requiring military intervention has arisen, even if that means recognising that previous forays may have contributed to the current crisis.

In addition to the myriad difficulties in developing a good narrative one requirement must underpin the process. Developing a useful narrative means taking a stand and that in turn requires understanding and accepting risk. It means that an organisation will have to publicly declare an alternative future that may not be acceptable to all. In some case the narrative will be required to directly disparage the future offered by the adversary. In development, identifying friction points and being prepared to exploit or mitigate them is crucial. The alternative approach of sanitising the narrative to the point that no one can find fault, defeats the purpose. A narrative is an item in which the immutable truths of a country, an organisation or an individual are proffered. This is perhaps the most difficult aspect in the complex operations the world currently finds itself in. Many ask how Australia, a multicultural, yet predominantly Christian nation, can effectively comment on the validity of Daesh’s interpretation of Islam? Daesh consistently argues that the model of faith they follow is the sole true interpretation of Islam. If we understand and decide that the brand of Islam Daesh propagates is extremist and negatively impacts our goals, we should be including aspects to directly counter our adversary. Not addressing the core elements of an adversary’s narrative leaves little room for a compelling alternative. Sometimes the ‘elephant in the room’ is an essential element of a counter-narrative. Thankfully, there are numerous Muslim scholars around the world who are equally disturbed by the perversion of the Islamic faith propagated by Daesh.

Building the narrative

Narrative development is an art, not pure science. Despite best efforts, there is no ‘narrative machine’ into which facts and intent are entered and a perfectly constructed paragraph is returned. There are, however, some basic requirements for a narrative to be pervasive. The first is recognising that good narrative expands beyond a single organisation and requires external input. Design by committee is always fraught with danger. So too is narrative creation in an interagency environment. However, to be a successful “core” for all communication efforts and to be useful in underpinning operational planning, wider understanding and acceptance is required. This means the development of a good narrative is also an educative effort for those participating in the process. This educative effort should keep returning to one thing — target audiences. It is they who are the focus of the communication efforts that naturally fall from a narrative, so by design, the words used must appeal to or, at the very least, be understood by them. In simple terms bureaucratic speak so favoured by committees; working groups and Tiger Teams is pointless. A narrative should link themes into a coherent story explaining to all “why we fight.”

The narrative is a living, breathing beast that must be adjusted as the campaign moves through its phases.

A narrative must be almost blunt in its simple use of language in order to ensure that when translated, its core principles survive. Blunt language, is of course, an anathema to bureaucracies and politicians and it is here that most issues arise. Similarly, the narrative must define what right looks like. It needs to be so prescriptive that the ‘promise’ of our narrative is something that can be observed and understood by all. Committing to a definitive outcome, against which actions and efforts can be measured and judged, is also a difficult concept. The narrative is a living, breathing beast that must be adjusted as the campaign moves through its phases. It needs to continually re-justify the actions needed to get towards the proposed future state — the promise we offer all.

The narrative has to be more than just a statement of facts arrayed to tell a story. It must offer a promise, a covenant between us and those who the narrative is directed at. It must invoke an emotional response because it becomes that basis from which targeted communication efforts designed to persuade and influence specific groups and individuals are based. Emotion is key in story telling and is crucial in gaining acceptance among target audiences. Rhetorical techniques are crucial in sustaining the argument for the proposed future state. The narrative needs to invoke the appropriate levels of support for putting personnel in harm’s way, for taking the lives of those who oppose us and, if required, a justification for destruction on a wholesale scale. Just restating facts will not achieve this. A good narrative is a psychological tool to generate and sustain support for our own cause and also to fracture support for our adversary.

Narratives must be based in reality. If our contribution is niche it needs to explain how that effort will support wider aims rather than attempting to frame campaign success as achievable by our efforts alone. If our participation has significant constraints, they should be acknowledged. If the outcome we seek is space for a partner to regroup and recommit to defending their population it should be stated rather than focusing on achieving world peace. A good narrative is not a series of jingoistic statements but instead, carefully considers the limitations inherent in our current contribution.

Finally, a narrative must be readily available. Creating a narrative and then assigning a security classification to it defeats the purpose of having a story to exploit. Yet we repeatedly do this with our predilection to over-classify everything that occurs on operations. We need our narrative to be contested in order for it to be continually refined and that means openly stating it. In fact our narrative, and the developed communication products that fall from it, should be displayed everywhere to continually remind targets audiences “why we fight.”

A possible narrative

Six months into operations in Iraq a number of possible narrative elements have arisen that were not fully obvious when forces deployed last year. The rise of ethno-religious militia groups and their centrality to security operations, the expansion of the conflict into countries beyond Iraq and Syria and of course the seemingly never-ending ways Daesh members have found to impose their brutality on people. These aspects highlight that a good narrative can’t be static. It must adjust with events as they unfold and in some ways should be pushed into action pre-emptively. Waiting for absolutely surety provides our adversary with the opportunity to impose and expand the reach and of his own dominant narrative.

So what is a possible narrative Australia’s ongoing fight against Daesh? As a first draft I offer the following for further development:

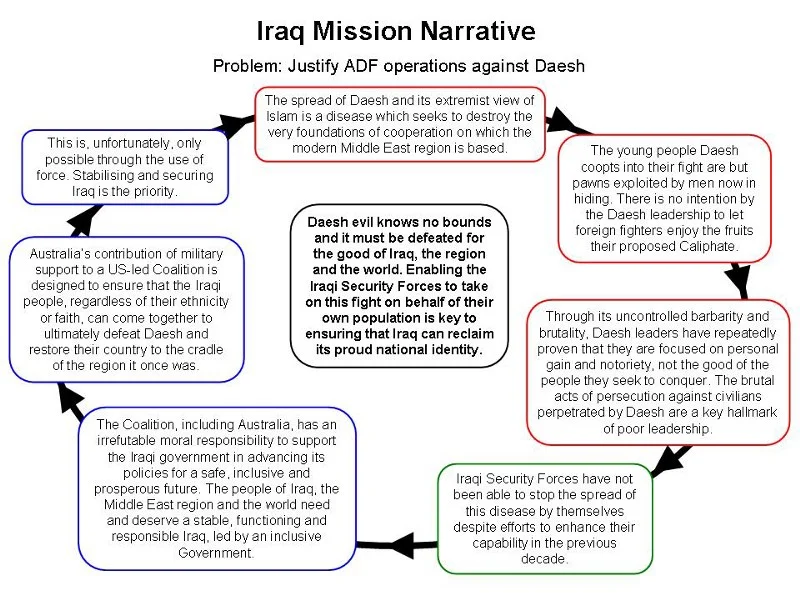

The spread of Daesh and its extremist view of Islam is a disease which seeks to destroy the very foundations of cooperation on which the modern Middle East region is based. Through its uncontrolled barbarity and brutality, Daesh leaders have repeatedly proven that they are focused on personal gain and notoriety, not the good of the people they seek to conquer. The brutal acts of persecution against civilians perpetrated by Daesh are a key hallmark of poor leadership. The young people Daesh co-opts into their fight are but pawns exploited by men now in hiding. There is no intention by the Daesh leadership to let foreign fighters enjoy the fruits their proposed Caliphate.

Iraqi Security Forces have not been able to stop the spread of this disease by themselves despite efforts to enhance their capability in the previous decade. The Coalition, including Australia, has an irrefutable moral responsibility to support the Iraqi government in advancing its policies for a safe, inclusive and prosperous future. The people of Iraq, the Middle East region and the world need and deserve a stable, functioning and responsible Iraq, led by an inclusive Government. Australia’s contribution of military support to a US-led Coalition is designed to ensure that the Iraqi people, regardless of their ethnicity or faith, can come together to ultimately defeat Daesh and restore their country to the cradle of the region it once was. This is, unfortunately, only possible through the use of force. Stabilising and securing Iraq is the priority.

Daesh evil knows no bounds and it must be defeated for the good of Iraq, the region and the world. Enabling the Iraqi Security Forces to take on this fight on behalf of their own population is key to ensuring that Iraq can reclaim its proud national identity.

Jason Logue is an Australian Army Information Operations specialist. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect those of the Australian Army, Australian Department of Defence or the Australian Government.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.