CNAS has recently published a report that offers some great suggestions to fix the wrong problem regarding leadership. Rich Ganske discusses the report and what it tells us about transformational leadership. The opinions expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent the US Air Force or the Department of Defense.

The Center for New American Security (CNAS) recently rolled out a provocative report titled,”Building Better Generals.” There are some valuable ideas to be considered here from LTG Barno, Dr. Bensahel, Ms. Sayler, and Ms. Kidder — especially on encouraging continued education for General and Flag Officers—and I recommend you take a look at it (see also, “’Building Better Generals’ Report Rollout Panel”)

However, the CNAS report really misses the true mark about what needs to be addressed in the military ranks: how to develop its future leaders. “Building Better Generals” spends the vast majority of its time focused upon what to do with the Generals and Flag Officers once they attain flag rank, which misses the real point of improving how the Generals and Flag Officers got there!

Intertwined within “Building Better Generals” you find some rich points for consideration in how the military can improve their officer and non-commissioned officers, rather than just focusing upon the immediate end-game concerns and risks of “ducks picking ducks.”

CNAS should have focused further upon one of the sidebars of the report titled “Corporate Best Practices.” To highlight one underemphasized anecdote from here: Barno et al, point out that “CEOs of high-performing companies spend a significant portion of their time — at least 25 percent—developing subordinate leaders; industry giants GE and Proctor & Gamble say that their CEOs spend 40 percent of their time developing other leaders.”

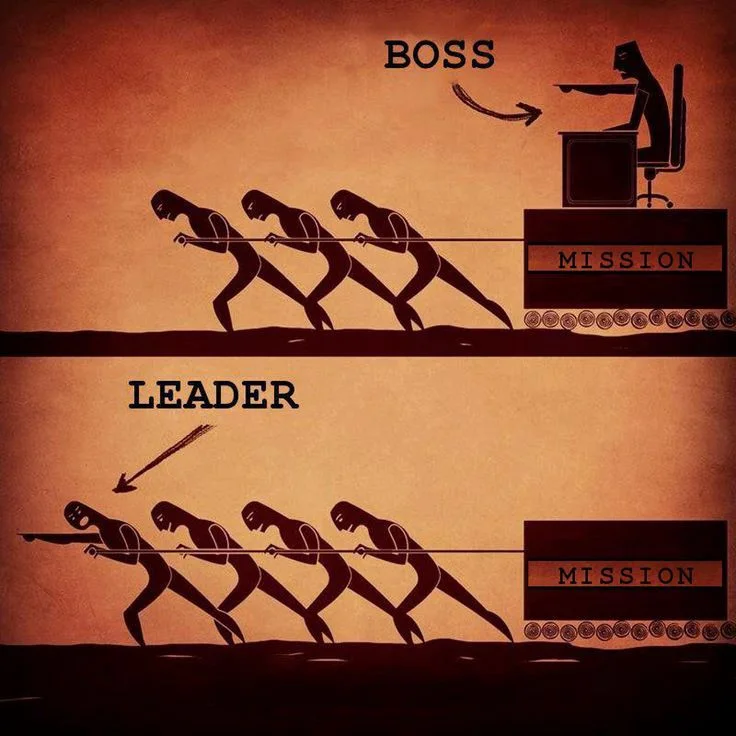

This anecdote within “Corporate Best Practices” means that these organizations made a systematic change towards transformational leadership development. While the military and business worlds differ immensely, they both tend to focus upon transactional relationships.Quid pro quo relationships highlight a linear expectation of progression in rank and responsibility: work the boss’s problem, and upon successful outcome, you’ll be rewarded. Transformational relationships, on the other hand, focus upon “deeper values and sense of higher purpose,” which ultimately leads to higher follower commitment and effort. Transformational leadership development creates non-linear outcomes for both the organization and its individuals.

Within transformational leadership an emotional connection, or rapport, is created between the leader and subordinate that forges tacit understanding of each others expectations, strengths, and weaknesses (for which the applications are boundless in terms of mission command, resiliency, sexual assault prevention, etc). The transformational leader can then best focus on those strengths and weaknesses towards the greater goal of the organization, or for the military, the mission. The leader/subordinate rapport is preeminent because it means that the subordinate can follow their own path to greater purpose, not just the path of the “anointed ones.”

There is no magic solution here, however it does require leaders to ask subordinates what they want to do, where they want to go, and what their story looks like. Then shut up and listen for a bit! LTG Barno, et al, might be surprised to find out that these stories will not conclude in a subordinate transitioning to operations, or lamenting the opportunities within the enterprise functions, or even the idiosyncratic path to making General or Flag Officer. The biggest mistake transactional leaders make is telling the subordinate their story instead of working together to align the subordinate’s story with the mission. The risk is time, the reward is transformation. Its not about where you have been and where you are, its about where they are going.

This focus upon rapport:

…looks beyond competencies, which have a tendency to focus on “what needs fixing,” and instead focuses attention on the whole person and on peoples’ strengths and natural talents, not on a reductionist list of idiosyncratic competencies. Development is increasingly seen as a process of developing and leveraging strengths and of understanding and minimizing the impact of weaknesses.

The common lesson here for both business and military, and most aptly for readers of “Building Better Generals,” is how to look beyond our organization’s idiosyncratic competencies and towards transforming our future leaders. Start by asking and listening to how subordinates want to get to wherever “there” is. That will build better Generals.

Rich Ganske is an Air Force officer, B-2 pilot, and weapons officer. He is currently assigned to the Army's Command and General Staff Officers Course at Fort Leavenworth. All views are his own. Follow him on Twitter: @richganske. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect any official organization.

Have a response or an idea for your own article? Follow the logo below, and you too can contribute to The Bridge:

Enjoy what you just read? Please help spread the word to new readers by sharing it on social media.